Erik Carter challenged participants at a Baylor University conference to be catalysts for change — so all really do belong in faith communities.

Carter is executive director of the Baylor Center for Developmental Disabilities, host of “Disability and Church: A Conversation” on April 17.

“How might we be communities of all the peoples — where members with and without disabilities live, learn, work and worship?” Carter asked. “And serve and support one another. … Where all families can flourish together in faith and life.”

Carted began with his personal testimony. Growing up in a time when disabled people generally were segregated in schools or clubs, he had limited opportunity to know and befriend people with disabilities.

“It was as if our schools, workplaces and even our churches were perfectly designed in ways that kept us apart,” Carter explained.

In this environment, Carter had come to believe his value lay in accomplishments and abilities — until he went to a summer camp his freshman year in college where he “stumbled into new friendships with several young men and women with intellectual disability at a mountain camping program.”

‘Glad abandon’ speaks

Wayne, Margaret and John Ray loved him without any concern for his accomplishments, and he felt belonging, Carter said. Beyond belonging, Carter observed the “glad abandon” with which they worshiped and their deep love for Jesus.

“John Ray could not speak, and Wayne often struggled with words,” Carter said. “They trusted wholeheartedly. They knew for sure they belonged to God. And how much I longed to have that same assurance! … And so, I followed their lead and gave my life to Christ.”

Carter said this story should not be surprising.

“Indeed, it is an ordinary story of how God’s grace flows through God’s people to transform lives. All of God’s people. No asterisks. No exceptions,” he noted.

Offering insights from two decades of research focused on “what it means to create communities in which believing and belonging abound together,” Carter described five prevailing portraits for community, which have generally progressed through history “from exclusion toward embrace.”

Portraits of community

Providing a visual model of each, Carter explained exclusion was the prevailing model of the 1970s, where individuals with disabilities still were excluded from much of community life — especially those with intellectual or developmental disabilities. There were holes in this model.

“Communities were incomplete,” Carter said.

In the 1970s and ’80s, separation was the prevailing model — where programs were created for children and adults with developmental disabilities, but “usually, apart from anyone else without the same label. In most communities, everyday life was still lived away from people with disabilities,” Carter said.

In the 1990s and 2000s there was a shift toward integration, “but many of the opportunities that emerged still involved a certain separation,” he said.

People with disabilities were placed “near, but not really among, their peers without disabilities. There is a huge difference between near and among,” Carter said.

The present-day model is one of inclusion, Carter said — “where a growing national focus is on the full inclusion of people with disabilities in the same classrooms, clubs, colleges, church activities and community groups as anyone else. Inclusion. From being apart to among and with one another.”

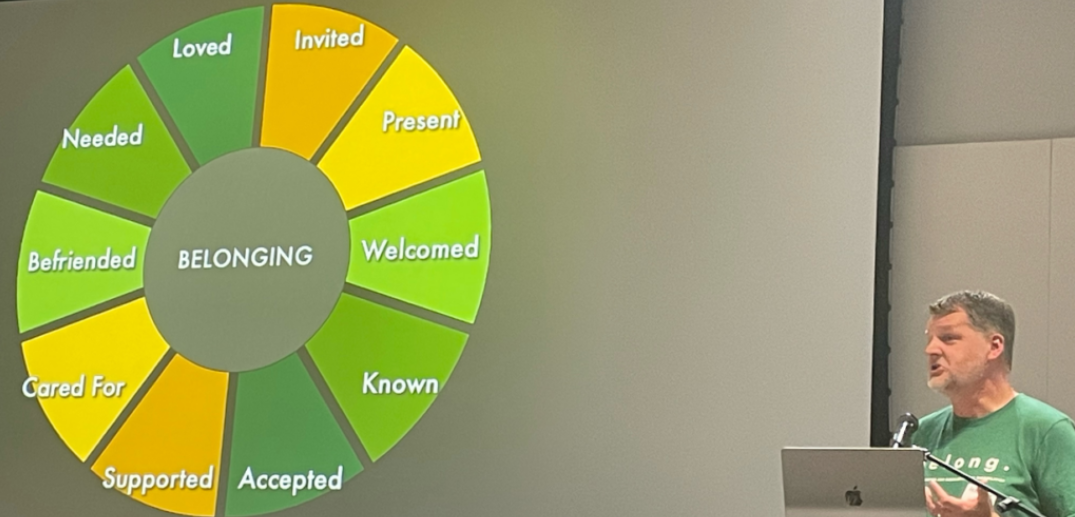

But, Carter said, there is still one more model churches should be striving toward — beyond integration or inclusion — belonging. In this model, Christians learn to see each other in fundamentally different ways, “as a diverse community in which each person has equal and immeasurable value … knitted together — woven into relationship.”

None of these models is actually just historical — it is “living history; our present landscape. … you will find each of these varied portraits — [exclusion, segregation, integration, inclusion and belonging] — across the more than 26,000 churches and scores of Christian schools throughout Texas,” Carter said.

But the research has identified elements of belonging, Carter said, “from the lived experiences of hundreds of young people with intellectual and developmental disabilities and their families who have been part of our various studies over the years.

“It is a question we have posed directly to them. How do you know you belong in your faith community?”

Elements of belonging

“Belonging is experienced when they are present, invited, welcomed, known, accepted, supported, cared for, befriended, needed and loved,” Carter said their responses showed.

Carter recalled his own testimony of being welcomed, befriended and loved by Wayne, Margaret and John Ray as a teen and how they shared their faith with others — people with disabilities doing ministry.

“Three people who might have been overlooked by society — and by the church — as a promising avenue through which Jesus might call others to him. And yet the opposite is certainly true,” Carter said, explaining that their gifts were real, attractive and a conduit for God’s life-changing grace.

Carter opened table talks, observed by Baylor Center for Developmental Disabilities representatives for the purpose of study. Participants reflected on and discussed ways the churches represented were doing well or could do better or differently in each of the ten areas identified as necessary for experiencing belonging.

Table discussions allowed families of disabled people and disabled attendees, themselves, to discuss their experiences with church and disability.

One participant, whose adult son is autistic, shared a positive story of inclusion at their church where they have been members for years.

She said everyone at church knows her son by name and that “she’s really only known as his mom.” They both feel known and loved there, she said.

But she said she would like to worship in a space where she feels less concerned about how an unexpected behavior from her son might impact other worshipers.

Vision becoming reality

She has a vision for beginning a disability-inclusive service, much like other churches might have non-English speaking language services. And one of her pastors and two other church members who want to help support and participate in this ministry vision becoming reality joined her for the talk.

Others at the table shared how their experiences at church had not always been welcoming. Kirk and Gena Baker shared of times they’d been asked to remove autistic children from worship, who were not being excessively disruptive.

They’ve forgiven these offenses, they said. But they expressed how crushing it was to be treated this way by brothers and sisters in Christ.

Yet they rejoiced in God’s answer to 27 years of prayer, when they moved to Waco less than two years ago and learned about the Baylor Collaborative for Developmental Disabilities beginning.

EDITOR’S NOTE — This story was written by Calli Keener and originally published by Baptist Standard.