“Why don’t people go to church? Because they’re dead.”

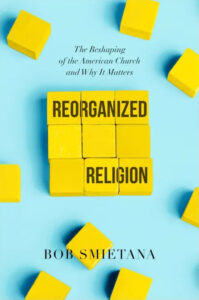

That unsettling quote, shared by author Bob Smietana during a keynote session of the recent Baptist Communicators Association annual workshop, is a stark reminder of how an aging population is impacting American congregations.

As more and more faithful church members graduate to heaven, fewer and fewer members of younger generations are taking their place in the pews (or folding chairs).

Smietana, a national reporter for Religion News Service, led the BCA session on “Reorganized Religion and Today’s Christian Communicator.” It played off of his recent book, “Reorganized Religion: The Reshaping of the American Church and Why It Matters,” released last year by Worthy Publishing.

Sharing statistics contrasting the Silent Generation’s Christian identity and church attendance to that of Millennials, Smietana said, “America’s grandparents go to church; their grandkids do not. America’s grandparents are white and Christian; their grandkids are not.

“These two groups of older and younger Americans live in what are essentially different universes when it comes to race and religion,” he added, “with different expectations of what the world should look like and who should be in charge.”

We all are familiar with organized religion and sometimes even disorganized religion. But what about reorganized religion? It’s a matter of recognizing and responding to the changing landscape of religion and society in healthy, redemptive ways that help the church both survive and thrive.

Citing a recent Pew Religion survey that found the percentage of self-identified Christians had dropped from 78% in 2007 to 63% in 2021, he said that number is projected to plummet below 40% by 2027.

Closer to home, he noted Southern Baptist church membership declined by more than 2 million during that same time frame.

“If you are doing more funerals than weddings,” Smietana pointed out, “your religious group is probably declining.”

One paradox — which he described as “the ‘Walmarting’ of churches in America” — is that while most churches are small, most people attend large churches (those with 250-plus in attendance).

A major challenge with that trend, he warned, is that in larger churches, participants typically “go less, give less, participate less.”

Side effect

A side effect of declining worship attendance in the majority of churches, Smietana added, is that “the people doing the work in your congregation are really tired.”

With many evangelical churches “filled with old, conservative, married people,” he said that means young, liberal singles typically don’t feel included or welcome. The same is true across ethnic, political and socioeconomic lines.

When “churches tell people they hate them” by their words, actions and attitudes, “they will believe you and not come,” Smietana cautioned. One pivotal concern is: Will churches simply write off those with whom they differ or actively seek ways to connect with and minister to them in the name of Christ?

Despite such overwhelming issues, Smietana affirmed that churches frequently find effective ways to navigate challenge and change.

Smietana’s book offers encouraging examples of churches that help their neighbors, comfort the grieving, visit the sick, laugh and rejoice together and pick up one another when they fall. “They keep the faith when all seems lost,” he wrote. “The question is: Will churches and other religious institutions choose to live?”

One key, he suggested, is to steadily practice one’s faith amid today’s rapidly changing world. That definitely is a redemptive response worth pursuing.

EDITOR’S NOTE — Trennis Henderson is regional correspondent for The Baptist Paper.